Sailing into the Christmas seas: The Greek “Karavaki” Tradition!

"Karavaki" (καραβάκι) in Greek literally translates to "little boat" or "small ship." It is a diminutive form of the word "karavi" (καράβι), which means "ship" or "boat." The suffix "-aki" in Greek is often used to denote something small or endearing, similar to "-ette" or "little" in English.

In Greece, a land cradled by the sea's vast embrace, the legacy of seafaring lives on. Even in today's fast-paced world, the Greek soul is still deeply intertwined with the rhythms of the sea. In many households, tales of fathers and sons who journeyed across the seas, 'aboard the ships' for livelihood, resonate even now.

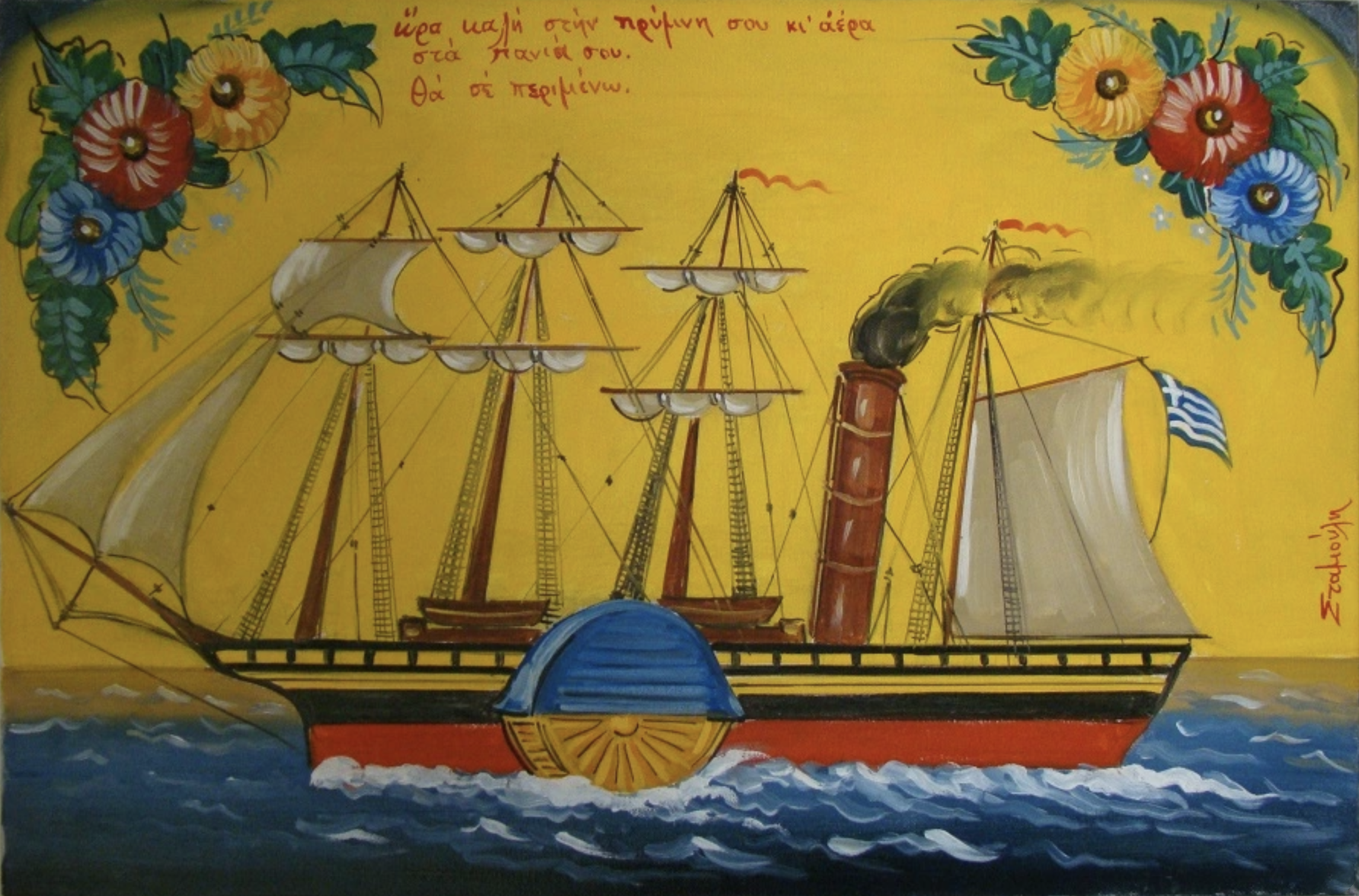

This maritime connection gains a special resonance during the Christmas season, a time earmarked for love and togetherness. Yet, often, the festive joy was tinged with the poignancy of missing family members, their lives intertwined with the sea's vast expanse. Amidst this backdrop, a heartwarming tradition flourished, particularly across the islands and coastal towns of the Aegean and Ionian Seas – the creation of the 'karavaki,' a miniature boat symbolising a myriad of sentiments.

The karavaki was more than just a decorative piece; it was a beacon of honour and a heartfelt welcome for the returning sailors. It symbolised a prayer, too, a hope for their safe navigation through the unpredictable waters. The Christmas karavaki, often a quaint wooden craft, was adorned with lights and festive ornaments, finding its place of pride beside the hearth or in the family yard. This tradition, commencing typically on 6 December in honour of Saint Nicholas, the protector of seafarers, saw these modest vessels become emblems of optimism and enduring hope.

Children in the Cycladic islands would engage in crafting their miniature boats from paper and wood. These small replicas, bedecked in vibrant papers and strings, were more than playthings; they were vessels of joy, filled with sweets and festive bread, as the children serenaded their neighbours with Christmas carols.

Notably, in the island of Chios, the tradition is vividly kept alive each New Year's Eve, with intricately replicated ship models, a testament to the skill and dedication of both the young and the old. These are not just any boats; they are a creative evolution from the simpler paper boats of the past, carried by enthusiastic carol singers of all ages, echoing wishes for the New Year.

The custom, with roots stretching back to the Balkan Wars and Chios' liberation, has evolved significantly over time. Particularly noticeable was the shift during 1912-1922, a period marked by historical upheaval. The boats, once made of paper, transformed into tin and later into tin cans, boasting improvised, ingenious systems. These allowed the miniatures to mimic real ships, complete with whistling funnels and firing miniature cannons. The carolers themselves embraced roles of a ship's crew, donning naval attire and caps, each playing a part - be it a captain, a stoker, a gunner, or sailors.

This tradition gained new life with the arrival of Asia Minor refugees in Chios. The carol singers, both young and old, began symbolically linking these boat models with warships, representing freedom, salvation, and the hope of returning home. The tradition also saw the emergence of special carols, echoing themes of war and refuge, often accompanied by traditional folk instruments like the clay 'tsambouka' and improvised drums.

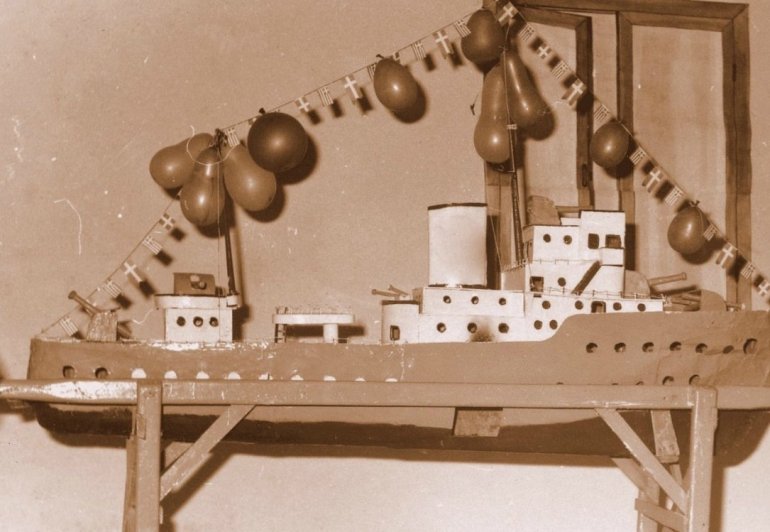

The advent of the 1970s brought a cultural shift, with the Christmas tree gradually taking the place of the traditional karavaki in Greek homes. However, the tradition saw a revival in 1976, reinventing itself as a competitive event. The competition to create the "most beautiful" ship model galvanized participation across communities. Teams, formed across different neighborhoods and comprising various age groups, worked under the guidance of experienced mentors. Their combined efforts focused on meticulous craftsmanship and teamwork, culminating in the creation of miniature ship models, each up to seven meters long, rich in detail and craftsmanship. Every year, these impressive models, now a fleet in their own right, parade through the city's central points. Illuminated and sometimes motorized, they compete for the top prize, accompanied by creative carols that add to the festive spirit.

In Ermoupolis, Syros, a similar scene unfolds. Here, the New Year's karavakia also pay homage to legendary warships. Crews are formed months in advance, each member playing a specific role, from handling gunpowder shells to playing in the orchestra. These karavakia, sometimes more than one in a year, parade through the town, visiting homes and spreading cheer with songs, music, and a collection of tips.

In both Chios and Syros, the theatrical karavaki displays merge naval history with festive cheer, keeping a rich tradition alive. This custom also thrives in other Greek regions, where karavakia now stand next to Christmas trees in public squares, marrying the old with the new. The karavaki, a staple in Greek homes during Christmas, offers a unique blend of warmth and nostalgia. It's more than just a festive symbol; it's a nod to a simpler time and a lasting echo of Greece's deep-seated maritime roots.